with Andy Parkes and Wayne Turner

In 1939 the 50th Division was organised as a Motor Division and served in France in 1940, taking part in the evacuation at Dunkirk. After escaping, it was re-organised as a Infantry Division in Britain. It was sent on 22 April 1941 to North Africa and was reinforced by the 69 Brigade from the disbanded 23rd ‘Northumbrian’ Division

North Africa and Sicily

The division saw service in the Desert Campaign, where it lost the 150 Brigade at Gazala. Under-strength, it took part in the retreat to El Alamein, acting in reserve. During the 2nd Battle of El Alamein it was positioned in the south. It was reinforced with the 1st Free French Brigade and 1st Greek Brigade for its planned attack on the Italian Folgore (Airborne) Division. It was supported by elements of the British 7th Armoured Division. Later in the battle it was transferred north to take part in Operation Supercharge.

In Tunisia the 50th Division assaulted the Wadi Akrit position, and was then involved in the Sicily landings of 1943, where it landed at Avola.

The 168 Brigade was attached from the 56th Division during the campaign.

In October 1943 the division was withdrawn to Britain for reforming and training before landing on D-Day. The 231 Brigade (an independent unit formed from regular troops stationed on Malta) were permanently attached, and the 56 Brigade was temporarily attached for the initial beach assault. Later the 56 Brigade was transferred to the 49th ‘West Riding’ Division.

D-Day

For D-Day the 50th Division was given the beach code named “GOLD” to land on. It covered an 8km area between la Riviére in the west to Le Hamel in the East. The German defences in this area were manned by the 4th Company 441. Ost Battalion (4/441 Ost) and 7/736 Grenadier Regiment belonging to the 716. Infanteriedivision, which were located on the east flank, and I Battalion/916. Grenadier Regiment of the 352. Infanteriedivision. Manning the marshy area between these two formations were elements of the 3/441Ost. Weapons in this area were 5cm PaK38 guns in open concrete emplacements and 7.5cm guns mounted within pill boxes.

To the rear were several artillery batteries covering the beach area (Mont Fleury, Creully, Crépon, Ryes and Marefontaine farm).

The role of the 50th Division was to establish a beachhead between Arromanches-les-Bains and Ver-Sur-Mer, then head towards Route Nationale 13 (RN13) linking Bayeux to Caen.

The first wave was made up of the 231 and 69 Brigades; once the assault was complete, the follow-up formations of 56 and 151 brigades would push inland towards RN13 supported by tanks of the 8 Armoured Brigade.

The assault started at 07.25 hrs on the “King” sector of Gold beach, almost an hour late. The Green Howards, came ashore supported by DD tanks of the 4th/7th Royal Dragoon Guards. Following a massive bombardment from HMS Warspite and HMS Ramilles, the assault came in from a distance of seven miles out, unlike the Americans who had deployed from twelve miles out. The DD tanks were not deployed out at sea, but they were landed directly on to the beaches. This meant that the assaulting troops had armour supporting them directly on the beaches.

The 8 Armoured Brigade supported the 69 Brigade with the 4th/7th Royal Dragoon Guards on the right flank directed on Riviére, and on the left the Sherwood Rangers Yeomanry supported the 231 Brigade at Le Hamel. The 24th Lancers were held in reserve to be landed later in the afternoon, but due to bad weather and congestion they did not land until 7 June.

Due to the shelved nature of the beach, the landing craft grounded early and the troops had to wade ashore. The defences in this area were weak and the troops easily subdued the defenders. They then pushed on inland to silence the gun batteries behind.

The battle for Le Hamel ground to a halt and casualties mounted, but direct support by the 147th Field Regiment, Royal Artillery (2nd Army) helped to reduce the strongpoint and it was finally taken at 16.00 hours.

By the end of the day nearly all of the 50th Division’s objectives had been captured. In the east contact was made with the Canadians South of Tierceville. The 69, 56 and 151 Brigades dug in on a line from Vaux-sur-Aure to Coloumbs. The 56 Brigade completed the day one mile short of Bayeux, 151 Brigade group reached the Caen-Bayeux road and the 69 Brigade had linked up with the Canadians and advanced a massive eight miles inland. The 7th Battalion, Green Howards had advanced so far they had to be pulled back to Coloumbs. Patrols from the 2nd Gloucester’s had reached the outskirts of Bayeux.

To the west, Arromanches was reached at 2000 hours and reported clear of enemy an hour later.

The men of the 47 Royal Marine Commando dug in on Hill 72 south of the Longues-Sur-Mer battery; their objective of the Port en Bessin would not fall until the 8 June, after serious heavy fighting.

Fighting Inland

The next day the bridgehead was enlarged, St Leger was captured and the leading elements of the Sherwood Rangers entered Bayeux to a warm reception.

8 June saw the 8 Armoured Brigade form a mobile column consisting of the 61 Recce Regiment, 1st Dorsets, 288 Anti-tank Regiment, RA, plus A Company of the Cheshire Regiment. An advance was ordered on a two-axis front with the 61 Recce Regiment on the right and 24th Lancers on the left.

On 7 June the 6th Green Howards had been ordered to advance and by 10.00 hours had passed through Rucqueville en-route for Ducy-Ste-Marguerite. Meanwhile the 7th Battalion Green Howards had begun an assault on the wireless station west of the Coloumbs-Loucelles road. The attack, conducted by the A and C Companies with B Company in support, was a complete success and resulted in 50-60 prisoners being taken. Both battalions then dug in and started receiving reinforcements and conducting fighting patrols in the area until 11 June when, the advance began again.

9 June saw A company 1st Dorsets, with 4/7 Dragoon Guards in support, moving through Audrieu south of the Caen rail line, while the Sherwood Rangers moved west around Audrieu to find an open flank. As the 8th Durham Light Infantry (DLI) became available, they were attached to the Sherwood Rangers and moved towards Point 103 mounted on the tanks. By 13.00 hours they were firmly ensconced on Point 103 and the 24th Lancers and 147th Field Regiment, RA were ordered to move up.

An attack was ordered on St Pierre for 17.30 hours using the 8th DLI and 4/7 Dragoon Guards, supported by self-propelled guns of 147th Field Regiment and machine-guns of the 5th Cheshires. A captured POW reported that St Pierre (1km east of Tilly-sur-Seulles) was lightly held, but it was found later that this was incorrect. It was finally cleared of enemy by 19.00 hours. By the evening of 9 June St Pierre was held and the 1st Dorsets along with the 4/7 Dragoon Guards were on Point 103.

10 June saw the 8th DLI being attacked by elements of Panzer Lehr Panzerdivision to try to clear the British from St Pierre.

Attacks were also directed to clear Point 103 from the west. By the afternoon all attacks had been beaten off with heavy casualties to the Germans (2 Tigers, 4 Panzer IVs, and 3 75mm SPs). In the evening an American liason officer arrived and gave the 50th Division access to a 155mm Artillery Regiment allowing targets to be engaged outside the range of 147th Field Regiment’s guns.

On 11 June an attack on Cristot to the East of Point 103 using 69 Brigade was planned against elements of 12. SS-Panzerdivision. The 7th Green Howards were to advance on the left flank to secure Brouay and make contact with the Canadians at Putot-En-Bessin. Meanwhile 6th Green Howards were to attack Cristot with support from 4/7th Dragoon Guards and 147th Field Regiment. The attack failed to capture its objective and stalled one field short of Cristot and the attack on Brouay failed to penetrate the defensive positions.

On 12 June further attacks were planned to extend the bridgehead, an attack on the Tessel-Bretteville feature was organised and carried out in the morning. It was to be a two-part attack with the first objective the high ground overlooking La Caude Rus, and the second part the Juvigny to Fontenay-Le-Pessel road. The first objective was captured, but further progress was stalled by Tigers and Panthers in the woods around Point 102. Meanwhile the 69 Brigade had tried to clear the woods between Cristot and St Pierre, but suffered heavy casualties.

Orders were then received for the 50th Division to hold the line from Point 103 to La-Belle-Epine, the 8th DLI were pulled back from St Pierre and the Sherwood Rangers were ordered to cover the withdrawal.

This left the 69 Brigade holding Point 103 with the 5th East Yorks in support, while the 146 Brigade (49th ‘West Riding’ Division) held the Loucelles road.

Tilly-sur-Seulles

With its infantry brigade still waiting to land, 22 Armoured Brigade of the 7th Armoured Division was sent forward to assist the 50th ‘Tyne and Tees’ Division in taking Tilly-sur-Suelles. The mission was to follow the 50th Division’s 56 Brigade and, once they had opened a hole in the line, to exploit it all the way to Villers-Bocage and then press on to Evrecy, deep in the German rear.

On 11 June the 50th Division attacked in the area of Tilly-sur-Seulles, Juvigny, Hottot-les-Bagues, and la Senaudiere, only to find the newly arrived Panzer Lehr Division also attacking head on into the same area. As the forces clashed the 7th Armoured Division moved forward in support. Even with their support, the attack stalled well short of its intended line.

After another attack on St Pierre on the evening of 11 June the town was abandoned. The 8 Armoured Brigade withdrew to rest and refit and their positions were taken over by the 49th Division, which allowed the 50th Division to concentrate on Tilly-sur-Seulles.

On 14 June they launched an attack led by the 151 and 231 Brigades supported by the 4/7 Dragoon Guards. The objectives were the villages of Lingévres and Verriéres. The 6th DLI took Verriéres and pushed south towards Hottot-les-Bagues. Once more they faced the Panzer Lehr’s Panzergrenadiers through the difficult bocage country, where the defenders were always at an advantage. The attack was supported by heavy air and artillery support. The 9th DLI advanced towards Lingévres. They soon came under fire from a large wood astride of their axis of advance. Heavy casualties were taken, but they were finally were able to advance through the wood into the village. The village was taken and defensive positions were organised against German counter-attacks. The inevitable counter-attack arrived and quickly knocked out four 6 pdrs, but the supporting 4/7 Dragoon Guards were more successful, knocking out six Panthers. The Germans attacked again at 1615 hours from the west. Three more Panthers were knocked out by the DLI anti-tank gunners.

The following day the attack was taken over by the 56 Brigade, who completed the capture of Tilly-sur-Seulles. On 15 June the 231 Brigade took Hottot-les-Bagues with the 1st Hampshires. A German counter-attack supported by tanks ejected them from their prize, and another attack was arranged with the 2nd Devonshires leading. The village was once again held by evening, but the brigade command withdrew the battalion as the hold on the village was not secure. This allowed the Germans to attack Tilly-sur-Seulles and re-occupy it. The town was finally taken on 17 June. In the meantime the 50th Division became bogged down, and little further progress was made for the rest of June.

Another push to take Hottot-les-Bagues was launched on 9 July, but was pushed back by the Germans. Another attack was arranged by 11 July to be carried out by the 231 Brigade supported by the Sherwood Rangers. It was supported by a massive rolling barrage. Progress was made, but the village was not taken. It wasn’t until 19 July, after the Germans had withdrawn across the whole division front, that the village was finally securely in British hands.

The next major action of the 50th Division was in August during Operation Bluecoat. XXX Corps (7th Armoured, 43rd and 50th Divisions) objectives were Villers-Bocage, Aunay-sur-Odon and finally Mont Pincon. The operation began on 30 July and initially progress was slow. The 50th Division was held up at Amaye-sur-Seulles.

The British pushed the front line back by 13km (eight miles), seized the German dominated high ground south of Caen and drove a wedge between the German Seventh Army and Panzer Group West. Mont Pincon was finally taken by the 43rd ‘Wessex’ Division on 6 August.

The operation was not strategically vital in itself, but it facilitated the US advance by concentrating the increasingly depleted German forces on the Caen area.

After France

The 50th Division was considered to have performed well in Normandy; in fact, out of the three divisions that were veterans of the desert (the others being 7th Armoured Division and 51st Highland) it performed the best. It was one of the driving forces behind the British advance. However, it was exhausted by the end of the battle.

It later played a minor role in Operation Market Garden, where the 231 Brigade was detached to help support the advance of Guards Armoured. The division stayed in northwest Europe until December 1944, when it was again returned to Britain, this time for the remainder of the war, and was converted into a training division. At the end of the war, it was sent to Norway and converted into British Ground Forces, Norway.

The Brigade

The Brigade

These core units were supported by an AA Troop with towed 40mm Bofors guns and an overworked and slightly under strength Engineer Company which was again expanded during the 1944/45 winter.

These core units were supported by an AA Troop with towed 40mm Bofors guns and an overworked and slightly under strength Engineer Company which was again expanded during the 1944/45 winter. The siege role ill suited the Czechs, who had insufficient manpower for the task and lacked the specialist engineering vehicles necessary to reduce the inland defences.

The siege role ill suited the Czechs, who had insufficient manpower for the task and lacked the specialist engineering vehicles necessary to reduce the inland defences.

The Siege

The Siege Despite the relatively static nature of the operation, the men of the CIABG were occasionally able to demonstrate their prowess and mobility in mobile battle. On 28 October 1944, elements of the 2nd Armoured Regiment and the Motor Battalion conducted a feint which drew defenders out from their prepared positions.

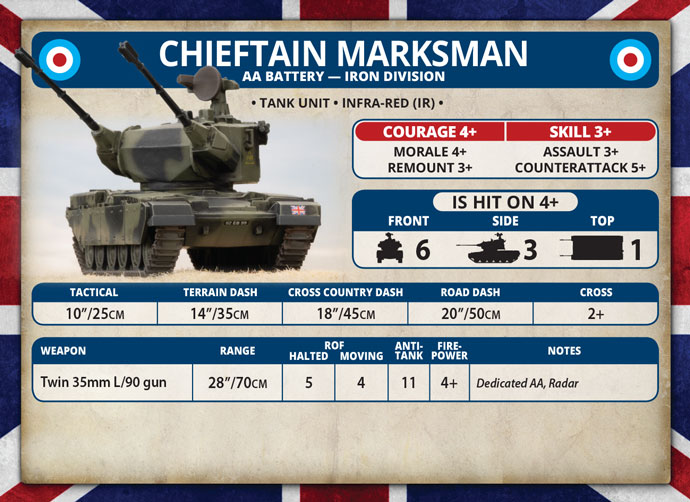

Despite the relatively static nature of the operation, the men of the CIABG were occasionally able to demonstrate their prowess and mobility in mobile battle. On 28 October 1944, elements of the 2nd Armoured Regiment and the Motor Battalion conducted a feint which drew defenders out from their prepared positions. One of the newest, most exciting weapons featured in the British Army book is the Marksman Self Propelled Anti Aircraft Gun (SPAAG). Following the Falklands War, Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher was livid at the losses sustained by the Royal Navy and the British Army, in part due to issues with the Rapier towed antiaircraft missile systems. Problems were experienced due to the need to “zero” the system and calibrate after each road move or unloading from a Naval landing craft. This meant valuable time of 15 minutes was wasted while cables were laid, stabilising of the sights and the calibration of the Blindfire radars was done.

One of the newest, most exciting weapons featured in the British Army book is the Marksman Self Propelled Anti Aircraft Gun (SPAAG). Following the Falklands War, Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher was livid at the losses sustained by the Royal Navy and the British Army, in part due to issues with the Rapier towed antiaircraft missile systems. Problems were experienced due to the need to “zero” the system and calibrate after each road move or unloading from a Naval landing craft. This meant valuable time of 15 minutes was wasted while cables were laid, stabilising of the sights and the calibration of the Blindfire radars was done. The Prime Minister jumped at the idea, especially when advised that 15 fire units of twin 35mm Oerlikon KDA guns that had been captured in perfect order from the Argentine Army and were still currently in use with RAF Regiment reservists of 1339 Royal Air Force Auxiliary Wing. These weapons were confiscated by Royal Ordinance Factory in short order and integrated with seven other sets of 35mm that were in testing along with the sole prototype unit. This gave the factory enough for seven batteries of three Marksman SPAAG’s as an initial production run. More guns would be forthcoming from Krauss Maffei who provided spares from their busy Gepard production lines.

The Prime Minister jumped at the idea, especially when advised that 15 fire units of twin 35mm Oerlikon KDA guns that had been captured in perfect order from the Argentine Army and were still currently in use with RAF Regiment reservists of 1339 Royal Air Force Auxiliary Wing. These weapons were confiscated by Royal Ordinance Factory in short order and integrated with seven other sets of 35mm that were in testing along with the sole prototype unit. This gave the factory enough for seven batteries of three Marksman SPAAG’s as an initial production run. More guns would be forthcoming from Krauss Maffei who provided spares from their busy Gepard production lines.

One of the many neat bits of kit you can find in D-Day: German is the Puma and its variants. To give you a bit of background on this unique beast before you bring it to the table we’ve unleashed another great historical article form the Flames Of War archive.

One of the many neat bits of kit you can find in D-Day: German is the Puma and its variants. To give you a bit of background on this unique beast before you bring it to the table we’ve unleashed another great historical article form the Flames Of War archive.

Of all the missions the Puma crew were assigned infiltration was the most difficult. Oberst a.D. Fabian von Bonin von Ostau explains: “The initial penetration into unknown enemy territory was difficult. For this purpose our own local attacks were taken advantage of before the enemy could recover his balance. When one had achieved some penetration, the advance became easier.”

Of all the missions the Puma crew were assigned infiltration was the most difficult. Oberst a.D. Fabian von Bonin von Ostau explains: “The initial penetration into unknown enemy territory was difficult. For this purpose our own local attacks were taken advantage of before the enemy could recover his balance. When one had achieved some penetration, the advance became easier.” The Puma were used to find the enemy, screen the flanks, and the companies were only used together in certain situations such as to screen the division during a withdrawal. According to Heinz Guderian they conducted “the ground reconnaissance for the panzer divisions they were assigned to. Only in open terrain, when being followed or to protect a withdrawal is the company used together.” The Puma performed well in its traditional roll and even showed strength on the attack.

The Puma were used to find the enemy, screen the flanks, and the companies were only used together in certain situations such as to screen the division during a withdrawal. According to Heinz Guderian they conducted “the ground reconnaissance for the panzer divisions they were assigned to. Only in open terrain, when being followed or to protect a withdrawal is the company used together.” The Puma performed well in its traditional roll and even showed strength on the attack. The Panzer division’s greatest enemy in Normandy proved to be the Allied fighter-bombers and the Pumas struggled with the foe as well. The stealth and infiltration techniques practiced by the Aufklärungs companies whose emphasis was on seeking cover during the day did help a high percentage of Pumas to survive the heavy damage the Panzer division took during Normandy. Of the original 26 Pumas from the Panzer Lehr division that started the campaign 8 survived Falaise Gap. In that same time only 20 tanks survived out of the starting strength of 109.

The Panzer division’s greatest enemy in Normandy proved to be the Allied fighter-bombers and the Pumas struggled with the foe as well. The stealth and infiltration techniques practiced by the Aufklärungs companies whose emphasis was on seeking cover during the day did help a high percentage of Pumas to survive the heavy damage the Panzer division took during Normandy. Of the original 26 Pumas from the Panzer Lehr division that started the campaign 8 survived Falaise Gap. In that same time only 20 tanks survived out of the starting strength of 109. The Normandy Campaign is well known for many battles and engagements in which the Wehrmacht was on both ends of the offensive onslaught that would mark the battle for northern France and the eventual breakout in late August. The early morning hours of 6 June 1944 would find the Germans mounting a determined resistance that would soon be forced back on it’s heels by the overwhelming material superiority that the Allied armies brought to bear.

The Normandy Campaign is well known for many battles and engagements in which the Wehrmacht was on both ends of the offensive onslaught that would mark the battle for northern France and the eventual breakout in late August. The early morning hours of 6 June 1944 would find the Germans mounting a determined resistance that would soon be forced back on it’s heels by the overwhelming material superiority that the Allied armies brought to bear. 2. Panzerdivision

2. Panzerdivision

Commanded by aristocratic Heinrich von Luttwitz, it was stationed at Amiens for refitting from January of 1944 as part of 15. Armee. On the eve of the invasion, the 2. Panzerdivision was several hundred men over strength and reported 94 operational Panzer IVs and 73 Panthers; a very strong division. In preparation for the invasion, the 2. Panzerdivision was put under direct command of Generalfeldmarschall Erwin Rommel. Only four divisions (2., 21., 116. and 130. Panzer Lehr Panzer divisions) were given to Rommel who suggested that the key to counterattacking the invasion, no matter where it came, was to have Panzer divisions rolling onto the Allied positions before they could establish a strong beachhead.

Commanded by aristocratic Heinrich von Luttwitz, it was stationed at Amiens for refitting from January of 1944 as part of 15. Armee. On the eve of the invasion, the 2. Panzerdivision was several hundred men over strength and reported 94 operational Panzer IVs and 73 Panthers; a very strong division. In preparation for the invasion, the 2. Panzerdivision was put under direct command of Generalfeldmarschall Erwin Rommel. Only four divisions (2., 21., 116. and 130. Panzer Lehr Panzer divisions) were given to Rommel who suggested that the key to counterattacking the invasion, no matter where it came, was to have Panzer divisions rolling onto the Allied positions before they could establish a strong beachhead. Panzerjägerabteilung attached to the 2. Panzerdivision, described it as “a hurricane of fire” which “raged through the countryside, wrapping everything in grey smoke and dirt.” (Hargreaves, pg.81)

Panzerjägerabteilung attached to the 2. Panzerdivision, described it as “a hurricane of fire” which “raged through the countryside, wrapping everything in grey smoke and dirt.” (Hargreaves, pg.81) The Normandy campaign gave the Panzerwaffe little time to rest between engagements, between the constant press of the enemy and Hitler’s frantic attempts to stem the tide. Perhaps most famous of his costly counterattacks was Operation Luttich, or “Liege”, named for a battle in World War I. The operation was to feature a three pronged assault to open a ten mile wide thrust behind the American armoured spearhead during Cobra, effectively isolating the attacking elements from their supply depots, as well as aiming to have the German lines reach the sea at Avranches. The divisions involved were to be the 2. and 116. Panzer divisions, the 1. and 2. SS-Panzer divisions as well as the 17. SS-Panzergrenadierdivision on the southernmost flank of the attack.

The Normandy campaign gave the Panzerwaffe little time to rest between engagements, between the constant press of the enemy and Hitler’s frantic attempts to stem the tide. Perhaps most famous of his costly counterattacks was Operation Luttich, or “Liege”, named for a battle in World War I. The operation was to feature a three pronged assault to open a ten mile wide thrust behind the American armoured spearhead during Cobra, effectively isolating the attacking elements from their supply depots, as well as aiming to have the German lines reach the sea at Avranches. The divisions involved were to be the 2. and 116. Panzer divisions, the 1. and 2. SS-Panzer divisions as well as the 17. SS-Panzergrenadierdivision on the southernmost flank of the attack.

Escaping through Falaise, it again had to rebuild and would later see action at Aachen and in the Ardennes campaign before it finally surrendered to the Allies in the Ruhr pocket.

Escaping through Falaise, it again had to rebuild and would later see action at Aachen and in the Ardennes campaign before it finally surrendered to the Allies in the Ruhr pocket. The 116. Panzerdivision, the “Greyhound Division”, was formed in March of 1944 in France. It was comprised of the 16. Panzergrenadierdivision and the 179. Panzer Reserve Division and was sent to Pas de Calais, north of the Seine River, in preparation for the Allied invasion.

The 116. Panzerdivision, the “Greyhound Division”, was formed in March of 1944 in France. It was comprised of the 16. Panzergrenadierdivision and the 179. Panzer Reserve Division and was sent to Pas de Calais, north of the Seine River, in preparation for the Allied invasion. The Greyhound division changed to a defensive role along the Vire River to hold the key road junction at Pontfarcy until 3 August. Their counterattacks were all but ignored by the surging US 2nd Armored Division. The 116. Panzerdivision, which up until that point had seen little but defeat, got its chance on 7 August as part of the 3 pronged attack of Operation Luttich. Initially successful due to heavy ground fog, the 116. Panzerdivision found itself being sent back to its jump off position within two days. When ordered to remount the attack, aristocratic commanding officer Generaleutnant Graf von Schwerin refused to send his men and tanks into battle, well aware of the danger to the German army as the Allies began to encircle their positions. Corps commander Freiherr von Funck who accepted no excuses, even ones that made sense, sacked Von Schwerin.

The Greyhound division changed to a defensive role along the Vire River to hold the key road junction at Pontfarcy until 3 August. Their counterattacks were all but ignored by the surging US 2nd Armored Division. The 116. Panzerdivision, which up until that point had seen little but defeat, got its chance on 7 August as part of the 3 pronged attack of Operation Luttich. Initially successful due to heavy ground fog, the 116. Panzerdivision found itself being sent back to its jump off position within two days. When ordered to remount the attack, aristocratic commanding officer Generaleutnant Graf von Schwerin refused to send his men and tanks into battle, well aware of the danger to the German army as the Allies began to encircle their positions. Corps commander Freiherr von Funck who accepted no excuses, even ones that made sense, sacked Von Schwerin.

By the end of the Normandy Campaign, the Wehrmacht’s panzer forces in the west had lost nearly all of their armoured units. Between the devastation of such places as Roncey, Falaise, the Seine River, as well as the Allied superiority in both the air as well as artillery, the Panzerwaffe suffered an insurmountable daily toll in the cost of both vehicles and men. The Germans were facing a materialschlact, a battle of attrition that cost the panzer divisions too much compared to their opponents. The Allies could afford to lose tanks as the massive material build up at the coast quickly replaced them, whereas the Germans felt every tank they lost and rarely received replacements. Instead vehicles were abandon in many cases when they could have been repaired if recovered. “The truth was that the Panzerwaffe, designed by its architects as a weapon of mobile strategic offence, was being steadily battered to pieces while performing a static tactical defence. Such counterattacks as it was able to make… were quickly halted and smashed up.” (Perrett, pg. 209). The cost would be astounding in both men and material.

By the end of the Normandy Campaign, the Wehrmacht’s panzer forces in the west had lost nearly all of their armoured units. Between the devastation of such places as Roncey, Falaise, the Seine River, as well as the Allied superiority in both the air as well as artillery, the Panzerwaffe suffered an insurmountable daily toll in the cost of both vehicles and men. The Germans were facing a materialschlact, a battle of attrition that cost the panzer divisions too much compared to their opponents. The Allies could afford to lose tanks as the massive material build up at the coast quickly replaced them, whereas the Germans felt every tank they lost and rarely received replacements. Instead vehicles were abandon in many cases when they could have been repaired if recovered. “The truth was that the Panzerwaffe, designed by its architects as a weapon of mobile strategic offence, was being steadily battered to pieces while performing a static tactical defence. Such counterattacks as it was able to make… were quickly halted and smashed up.” (Perrett, pg. 209). The cost would be astounding in both men and material.

The best German infantry units based in France in 1944 were the regiments of the Fallschirmjägerdivisions or parachute divisions. Although they were actually Luftwaffe troops, these units were by this time in the war, tactically subordinated to Army command.

The best German infantry units based in France in 1944 were the regiments of the Fallschirmjägerdivisions or parachute divisions. Although they were actually Luftwaffe troops, these units were by this time in the war, tactically subordinated to Army command. II. Fallschirm-Korps, commanded by General Eugen Meindl, was allocated by the Commander of the Western Theatre, Field Marshal Gerd von Rundstedt, to the Seventh Army, commanded by General Friedrich Dollmann, in Brittany. It would in May 1944 be made up of the following units:

II. Fallschirm-Korps, commanded by General Eugen Meindl, was allocated by the Commander of the Western Theatre, Field Marshal Gerd von Rundstedt, to the Seventh Army, commanded by General Friedrich Dollmann, in Brittany. It would in May 1944 be made up of the following units: 2. Fallschirmjägerdivision and 5. Fallschirmjägerdivision were by comparison, poorly trained, undermanned and badly equipped. However, they too fought with the esprit-de-corps of all Fallschirmtruppen and helped forge a combat reputation respected by all Allied opponents.

2. Fallschirmjägerdivision and 5. Fallschirmjägerdivision were by comparison, poorly trained, undermanned and badly equipped. However, they too fought with the esprit-de-corps of all Fallschirmtruppen and helped forge a combat reputation respected by all Allied opponents. 6. Fallschirmjägerregiment was arranged as follows:

6. Fallschirmjägerregiment was arranged as follows:

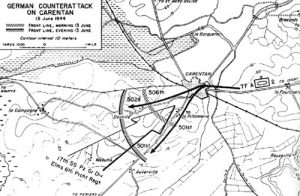

At first the advances made good time, but by midnight both battalions were in heavy contact just short of their objectives. 1. Bataillion found the US paratroopers at St. Marie-du-Mont had linked up with the 4th Infantry Division moving inland from Utah beach. Earlier in the evening and again before dawn on 7 June waves of American gliders and paratroopers began to drop across the entire combat area, and the two battalions, found themselves low on ammunition and increasingly cut-off from the Regimental rear areas.

At first the advances made good time, but by midnight both battalions were in heavy contact just short of their objectives. 1. Bataillion found the US paratroopers at St. Marie-du-Mont had linked up with the 4th Infantry Division moving inland from Utah beach. Earlier in the evening and again before dawn on 7 June waves of American gliders and paratroopers began to drop across the entire combat area, and the two battalions, found themselves low on ammunition and increasingly cut-off from the Regimental rear areas. On 8 June St. Come du Mont was defended by III. Bataillon, 1058. Regiment, 91. Luftlandedivisionand two companies from III. Bataillon, 6. Fallschirmjägerregiment. Against them the Americans launched the 1st and 2nd Battalions, 506th PIR, 3rd Battalion 501st PIR, 3rd Battalion, 327th Glider Infantry, 8 light tanks and the 65th Armoured Field Artillery Battalion.

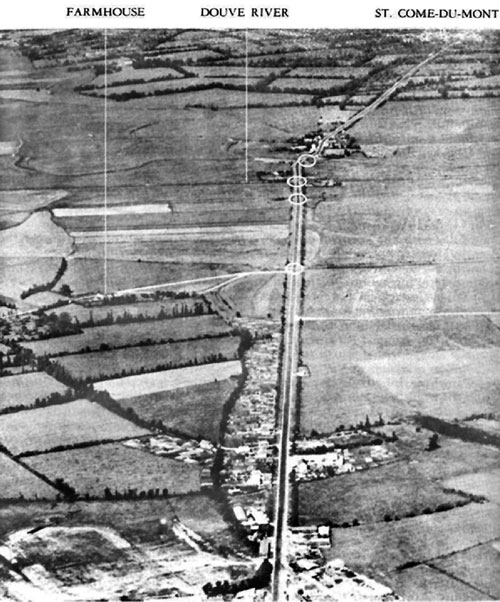

On 8 June St. Come du Mont was defended by III. Bataillon, 1058. Regiment, 91. Luftlandedivisionand two companies from III. Bataillon, 6. Fallschirmjägerregiment. Against them the Americans launched the 1st and 2nd Battalions, 506th PIR, 3rd Battalion 501st PIR, 3rd Battalion, 327th Glider Infantry, 8 light tanks and the 65th Armoured Field Artillery Battalion. In the mid afternoon of 10 June men from the 3rd Battalion, 502nd PIR advanced in single file down the causeway. They soon came under heavy machine-gun fire from the Fallschirmjäger in a farmhouse and bocage which took a heavy toll on the US paratroopers. The fourth bridge was also blocked by a Belgian Gate, which meant, just one man could squeeze through at a time. The Americans were held at this point until past midnight, when they were able to filter men past the barricade.

In the mid afternoon of 10 June men from the 3rd Battalion, 502nd PIR advanced in single file down the causeway. They soon came under heavy machine-gun fire from the Fallschirmjäger in a farmhouse and bocage which took a heavy toll on the US paratroopers. The fourth bridge was also blocked by a Belgian Gate, which meant, just one man could squeeze through at a time. The Americans were held at this point until past midnight, when they were able to filter men past the barricade.

At 0630 hours on 22 July after a heavy artillery barrage 358th Regiment of 90th Infantry Division breached the forward lines of III. Bataillon, 6. Fallschirmjägerregiment penetrating more than a 800 yards inside German lines. But here there was little cover for the advancing American troops and they came under a steady crossfire. Around midday, von der Heydte ordered his 16. Kompanie, commanded by Oberfeldwebel (Sergeant) Alexander Uhlig to counterattack the Americans, re-establish the German main line of defence, and if possible capture a couple of prisoners.

At 0630 hours on 22 July after a heavy artillery barrage 358th Regiment of 90th Infantry Division breached the forward lines of III. Bataillon, 6. Fallschirmjägerregiment penetrating more than a 800 yards inside German lines. But here there was little cover for the advancing American troops and they came under a steady crossfire. Around midday, von der Heydte ordered his 16. Kompanie, commanded by Oberfeldwebel (Sergeant) Alexander Uhlig to counterattack the Americans, re-establish the German main line of defence, and if possible capture a couple of prisoners. The first assault began around 0700 on 23 July, and it took two more attacks to break the Americans. Down to just one panzer by this time, the third assault broke through to the 1st Battalion’s command post and the men of that unit began to fall back in panic or surrender. Many of those that retreated were cut down by the two emplaced MG 42s who now opened fire.

The first assault began around 0700 on 23 July, and it took two more attacks to break the Americans. Down to just one panzer by this time, the third assault broke through to the 1st Battalion’s command post and the men of that unit began to fall back in panic or surrender. Many of those that retreated were cut down by the two emplaced MG 42s who now opened fire. In the desperate winter of 1941, the Heer, the German Army, was on the defensive after its failed advance on Moscow. Every available unit was thrown into the battle, including the Luftwaffe Fallschirmjäger (air force paratroops). One such unit was the Luftlandesturmregiment, Air-landing Assault Regiment, under Generalmajor Meindl. The regiment’s casualties were so severe that it was withdrawn early in 1942.

In the desperate winter of 1941, the Heer, the German Army, was on the defensive after its failed advance on Moscow. Every available unit was thrown into the battle, including the Luftwaffe Fallschirmjäger (air force paratroops). One such unit was the Luftlandesturmregiment, Air-landing Assault Regiment, under Generalmajor Meindl. The regiment’s casualties were so severe that it was withdrawn early in 1942. By the spring of 1942, the Army’s need for troops to replace its casualties was so acute that they convinced Hitler to transfer surplus troops from the Luftwaffe to the Heer. Reichsmarshall Herman Göring, Commander In Chief of the Air Force, was furious. Not only would his personal empire be diminished, but also the reactionary Army, the very organisation responsible for the failures of the previous year, would corrupt his loyal National Socialist airmen.

By the spring of 1942, the Army’s need for troops to replace its casualties was so acute that they convinced Hitler to transfer surplus troops from the Luftwaffe to the Heer. Reichsmarshall Herman Göring, Commander In Chief of the Air Force, was furious. Not only would his personal empire be diminished, but also the reactionary Army, the very organisation responsible for the failures of the previous year, would corrupt his loyal National Socialist airmen. Luftwaffe field divisions were approximately half the size of their Heer counterparts.

Luftwaffe field divisions were approximately half the size of their Heer counterparts. 2. Luftwaffe Felddivision (Oberst Hellmuth Pätzold)

2. Luftwaffe Felddivision (Oberst Hellmuth Pätzold) 4. Luftwaffe Felddivision (Oberst Hans-Georg Schreder)

4. Luftwaffe Felddivision (Oberst Hans-Georg Schreder) 7. Luftwaffe Felddivision (Generalmajor Wolf Freiherr Von Biedermann)

7. Luftwaffe Felddivision (Generalmajor Wolf Freiherr Von Biedermann)

10. Luftwaffe Felddivision (Generalmajor Walter Wadhehn)

10. Luftwaffe Felddivision (Generalmajor Walter Wadhehn) 11. Luftwaffe Felddivision

11. Luftwaffe Felddivision 17. Luftwaffe Felddivision

17. Luftwaffe Felddivision Between then and December 1942, when 21. Luftwaffe Felddivision was formed, the division was reunited and held the southern flank of the newly opened corridor to Demyansk and Cholm. The newly formed division only had four regiments, the fifth having been disbanded. It gained an artillery regiment with French guns in the summer of 1943, along with an assault gun battery of four long-barrelled StuG III assault guns (increased by a further six StuG IV in 1944) and ten 7.5cm PaK40 guns. Each regiment was also reported as having as many as ten 7.62cm PaK36(r) anti-tank guns. At this point it was easily the strongest Luftwaffe field division in existence.

Between then and December 1942, when 21. Luftwaffe Felddivision was formed, the division was reunited and held the southern flank of the newly opened corridor to Demyansk and Cholm. The newly formed division only had four regiments, the fifth having been disbanded. It gained an artillery regiment with French guns in the summer of 1943, along with an assault gun battery of four long-barrelled StuG III assault guns (increased by a further six StuG IV in 1944) and ten 7.5cm PaK40 guns. Each regiment was also reported as having as many as ten 7.62cm PaK36(r) anti-tank guns. At this point it was easily the strongest Luftwaffe field division in existence. The division was involved in heavy fighting from March 1944 until it surrendered in the Courland pocket at the end of the war.

The division was involved in heavy fighting from March 1944 until it surrendered in the Courland pocket at the end of the war.