After their experience on the Don River in the winter of 1942/43 the Hungarians instituted a number of changes to their infantry forces in 1943. The first of these reforms was known as the Szabolcs I plan and was updated in early 1944 to the Szabolcs II plan. The new infantry divisions were based around three 3-battalion infantry regiments (the forces on the Don were two regiment light divisions). They were upgraded with heavier artillery, replacing the old 80mm field guns with 100mm howitzers and reinforced by 149mm howitzers. An effort was made to obtain heavier anti-tank weapons such as the 75mm PaK40 from the Germans and each infantry regiment was issued with nine of these. Another lesson learned from the Germans was the need for the infantry to have their own armour and the Assault Artillery was formed with the intention to have a battalion of Zrínyi assault howitzers available to each infantry division.

After their experience on the Don River in the winter of 1942/43 the Hungarians instituted a number of changes to their infantry forces in 1943. The first of these reforms was known as the Szabolcs I plan and was updated in early 1944 to the Szabolcs II plan. The new infantry divisions were based around three 3-battalion infantry regiments (the forces on the Don were two regiment light divisions). They were upgraded with heavier artillery, replacing the old 80mm field guns with 100mm howitzers and reinforced by 149mm howitzers. An effort was made to obtain heavier anti-tank weapons such as the 75mm PaK40 from the Germans and each infantry regiment was issued with nine of these. Another lesson learned from the Germans was the need for the infantry to have their own armour and the Assault Artillery was formed with the intention to have a battalion of Zrínyi assault howitzers available to each infantry division.

As war continued to push closer the Hungarian border, provisions were made for mobilising more forces in the form of Reserve or Replacement divisions. These were formed along the same organisation as the first line divisions, but usually had less artillery available, with just three instead of four battalions, and no assault artillery battalion.

The Mountain Border Police were mobilised in times of war to provide the two Hungarian Mountain Brigades and new Border Guard units were raised to replace them. The Border Guard came under the Army and also patrolled the borders in peacetime, but they also provided fortress companies for the guarding of strategic passes and fought if Hungary was invaded.

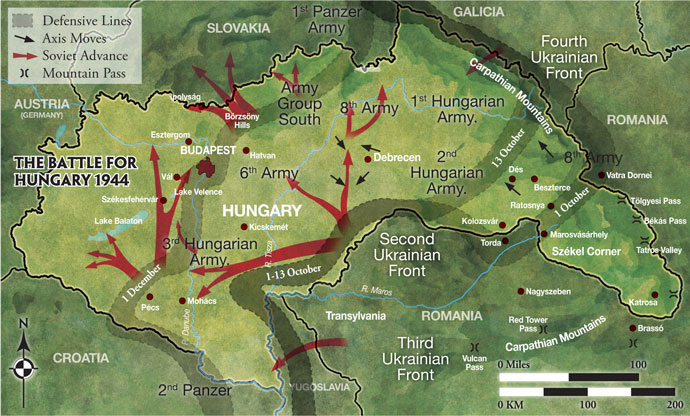

The Székler Command has it roots in the traditions of the Austro-Hungarian empire, which had a tradition of keeping irregular light border troops to harass any invading enemy (usually the Ottoman Turks). The Székely are the ethnic Hungarian people of Transylvania. During World War II their responsibility was the Székel Corner, the part of Hungary known as Northern Transylvania that jutted out over the Romanian controlled territory of the rest of Transylvania. Because of the way Transylvania was divided in 1940 the border had no natural features on which to anchor the border defence and defence in this sector became a difficult prospect. It had only been linked by rail to the rest of Hungary in 1942. The Székler Command was made up of a mix civilian Border Police, army Border Guard and local militias whose responsibilities included the defence of any passes and roads navigable by enemy tanks in the Carpathian Mountains. Because of its isolated position the Székel Corner was supplied with ammunition and provisions for four weeks fighting in case it was cut-off, as well as food stockpiles for the civilian population.

Fighting for the Székel Corner

The Romanians changed sides after their defeat by the Soviets in the battles for Iaşi and Chişinău in August 1944 and the threat of invasion became an imminent reality. As early as 10 August Lieutenant-General vitéz (meaning brave, an honourary title somewhat like a knighthood) Lojos Veress, commander of the Hungarian Second Army, with the IX Corps at Kolozsvári (Cluj) in Northern Transylvania, held a meeting with his senior commanders and German Generalmajor von Grolman, the chief of staff of Army Group South Ukraine, to discuss the defence of the Eastern Carpathians. The original defensive plan had been made with Romania still allied with the Germans, but new provisions had to be made with the threat of the Romanians attacking from Southern Transylvania.

The first Romanian probe into Hungarian territory occurred on 25 August, west of the Moras (Mures) River, when a battle group of Romanian infantry crossed the border in the Keleman (Călimani) Mountains on the northwestern edge of the Székel Corner and clashed with the 23rd Border Guard Battalion and local Gendarmes (rural police).

A day later more serious fighting broke out when elements of the Soviet 7th Guards and the 23rd Tank Corps crossed the border into the Úz and Csobányos valleys and north from the Ciuc Mountains, bringing the fighting proper to Hungarian soil for the first time in the war.

Some German units had arrived to join the fighting, with Kampfgruppe Abraham and Kampfgruppe Fessner joining the defence. However, it became clear that the Hungarian border forces were not going to be enough to hold back the might of the Red Army. Hungarian units had begun mobilising in central Hungary with the Second Army mobilising as further troops were sent to aid the IX Corps fighting in Transylvania. The VII Corps headquarters was detached from the First Army, which was fighting on the border with the Ukraine, and given command of the 25th Infantry Division, 20th Infantry Division and the 2nd Armoured Division, all veteran units who had been fighting in the Ukraine since April. The Second Army was further boosted by troops quickly raised as part of the field replacement army, including the 2nd Field Replacement Division.

Retreating German units increasingly joined the fighting and the 4. Gebirgsdivision was transferred from the north to join the defence of Transylvania. With only border troops immediately available the Germans played an important role in the fighting around the Baróti Mountains, at Nyárád and holding the Maros (Mures) River and Szászrégent (Reghin) line and at Marosludas (Luduş) up until the beginning of October 1944.

The Ojtózi Pass held for several days, but was lost when the 24th Border Guard Battalion was forced out the southeast corner of the front line, but with the aid of German units they were able to halt the advance until 9 September along the Ojtózi (Ozsdola) − Berecki (Bereck) − Lemhény (Lemnia) − Torja (Turia) − Kászonújfalu (Caşinu Nou) line. The 24th Border Guard Battalion and 67th Border Guard Group’s determined defence played an important role. During these battles there were outstanding displays of fighting by the Hungarian border troops.

At no other time during the war had three Hungarian officers from the same company received an honour for the same action.

In another outstanding action reserve Ensign Ferenc Mező commanded the machine-gun company of the 24th Border Guard Battalion defending the area between Kászonjakabfalva, the 1,051 metre Nyir peak, and the village of Katrosa on 3 September. During the day his positions repelled several Soviet infantry and cavalry attacks. Mező took command of the last machine-gun after its crew had been lost, and, already wounded himself, he beat back several more Soviet infantry assaults. Armed with nothing but his resolute determination he held his position with hand-to-hand fighting all around him. He died fighting off Soviet infantry, unwilling to retreat. He was posthumously awarded the Officers Gold Medal for Bravery, the 17th officer to be so awarded during the war.

The Soviet 50th Guard Rifle Corps, of the 40th Army, sent patrols into Hungary on 3 September to the north and south of the Békás (Bicas) pass. They headed north to the heights at Point 1502 to increase pressure on the hard-pressed Hungarians. If the Soviets were able to take possession of this commanding elevation, they planned to then take the Békás and Tölgyesi passes and at the same time the 1078 meters high pass at Balázsnyakát where the road between Gyergyóbékás (Bicazu Ardelean) and Gyergyótölgyes (Tulgheş) crossed. The positions of the 1st Székely Mountain Border Battalion were supported by the 21st Mountain Battery with four guns. Also in the area was the 21st Border Guards Battalion, which also had a four-tube mortar platoon, two German mortars and a German field artillery battery. The key figure in the defence was the commander of the 21st Mountain Battery, Lieutenant Vilmos Brambring.

Meanwhile, the areas beyond the Tölgyesi Pass action was also reinforce by the IX Corps. As a consequence a battalion of the 2nd Field Replacement Division was sent to Gyergyószentmiklósi and arrived around midnight at the train station.

The Kelemen Mountains in the east of Northern Transylvania had not yet been threatened, but on 1 September, the Beszterce 22nd Border Guard Battalion and two battalions of the Kosnánál Székely Border Guards crossed the border by rail into Vatra Dornei. There, the Germans had formed a bridgehead, based around an important manganese ore mine.

Having done all that they could to hold Northern Transylvania, on 7 September the Hungarians and Germans began to evacuate the area. Any plans for the capture the passes of the Carpathians before the Soviets could had proved utterly illusory. The German Sixth and Eighth Armies, and Hungarian Second Army, under the headquarters of German Army Group South Ukraine, withdrew in several phases due to the space limitations.

As a result, by roughly mid-September a new defensive position was establishment on the Moras River. The superior firepower of German mobile battle groups was used to cover the withdrawal of the marching infantry columns of shattered Hungarian frontier units. From 16 September battalions arriving in good order were redeployed along the Kelemen and Görgényi mountains and at the Ratosnyai Gorge on Maros River. During this period the Germans took operational command of all the Hungarian units of the IX Corps and Székely Border command, for both tactical and political reasons.

On 12 October 1944 in the area of Ratosnya (Răstoliţa) − Beszterce (Bistriţa) − Dés (Dej) − Szászrégen (Reghin) bordering Northern Bukovina more heavy fighting took place. The Székely 27th Light Division was redirected to halt the Soviet advance, but they could do little to stop the Soviet mechanized and armoured force. All the lightly equipped division could do was delay them.